Where I live, we just recently had our seventh fire alarm (1) pulled in the past two months (2). So at four in the morning, when I was deciding if it was a prank  or real and whether or not I needed to get out of bed (3), I thought to myself, “What could possibly make people want to pull the fire alarm so badly? And who the heck (4) would design such a terrible torture device?” The alarm turned out to be because of the faulty kitchen in the common area, again, but the questions stuck with me.

or real and whether or not I needed to get out of bed (3), I thought to myself, “What could possibly make people want to pull the fire alarm so badly? And who the heck (4) would design such a terrible torture device?” The alarm turned out to be because of the faulty kitchen in the common area, again, but the questions stuck with me.

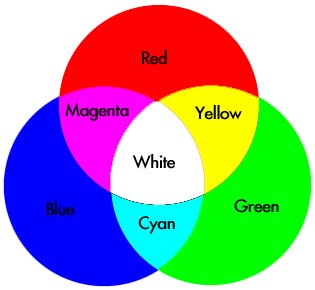

My guess for the first question is that the clearly printed words, “Pull Down” or “Push In, Pull Down,” working in  conjunction with the color red, and the big, downward pointing arrows, have something to do with it (see images). Then again, it might be that tendency for kids in my age demographic to be self-destructive. As a good friend asked me last year, “Have you ever been driving and wanted to suddenly turn into the other lane (the one with oncoming traffic) as a car is coming?”

conjunction with the color red, and the big, downward pointing arrows, have something to do with it (see images). Then again, it might be that tendency for kids in my age demographic to be self-destructive. As a good friend asked me last year, “Have you ever been driving and wanted to suddenly turn into the other lane (the one with oncoming traffic) as a car is coming?”

As for the second question, “Who designed the fire alarm?” the answer is Francis Robbins Upton, who did it in 1890 (5). It was not until the 1930s, though, that the smoke detector was (accidentally) invented by Walter Jaeger; smoke detectors and fire alarms tend to go hand in hand. By the late 1960s, fire alarms/smoke  detectors were out on the commercial market, and are now present in about 93% of US homes and you are reportedly twice as likely to survive a house fire if you have one (same site as 5). I appreciate that fire alarms are here to save my life, but could they please do it sometime other than 4am?

detectors were out on the commercial market, and are now present in about 93% of US homes and you are reportedly twice as likely to survive a house fire if you have one (same site as 5). I appreciate that fire alarms are here to save my life, but could they please do it sometime other than 4am?

(1) It might actually be eighth. My roommates and I are keeping a tally, but there’s a chance we all were gone when one happened.

(2) Yes, I do live in the dorms.

(3) You tend to get a bit jaded…

(4) You’re right…”heck” was not the word I was thinking at 4 in the am.

(5) I browsed the net for 20 minutes and his was the name that appeared most frequently. I would’ve preferred to use a book source, but alas, I have no books about fire alarms handy. Here’s the most helpful page: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smoke_detector

Top Fire Alarm Pull: http://ballyhooligan.files.wordpress.com/2009/04/fire_alarm.jpg

Bottom Fire Alarm Pull: http://www.firelite.com/images/bg12.jpg

Smoke Detector: http://www.smokedetectorsonline.com/images/smoke_detector.jpg